Is there a shortage of ayahuasca in the jungle? Chris Kilham, founder of Medicine Hunter, presented his paper “The sustainability of ayahuasca, from vine to cup” at the 2019 World Ayahuasca Conference in Girona, Spain. Kilham referenced the research he conducted in 2018 in the regions of Pucallpa and Iquitos in Peru, epicenters of ayahuasca tourism worldwide, to better understand the supply and cultivation status of the ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis caapi). Kilham’s findings were published in the scientific journal Herbal Gram.

“Only once during the 22 years I have been studying ayahuasca in Peru have I encountered a person who has said to me ‘we have problems with the supply’ of the vine, although this shortage does occur more commonly in the case of chacruna (Psychotria viridis),” Kilham explained.

According to Kilham, the concept of an increasing ayahuasca shortage in Peru was propelled by a report published in 2017 by The Guardian. This “constant stream of speculation” has been going on without “any studies to back it up.” “That’s when I decided to get my team in Peru together to answer the question of whether or not there is a shortage of the vine in Peru, who is growing it, and how much is being cultivated.”

Ayahuasca supply and demand

Kilham’s team conducted their research in the Loreto and Ucayali departments of Peru in 2018. He stated, “In Iquitos, we have 120 ayahuasca centers in operation. There is also an increase in retreat centers in Pulcalpa because the locals prefer to open them there instead of leaving their families to go to Iquitos.” Kilham acknowledged that “shamans are emerging from nowhere” to meet the demand for ayahuasca tourism.

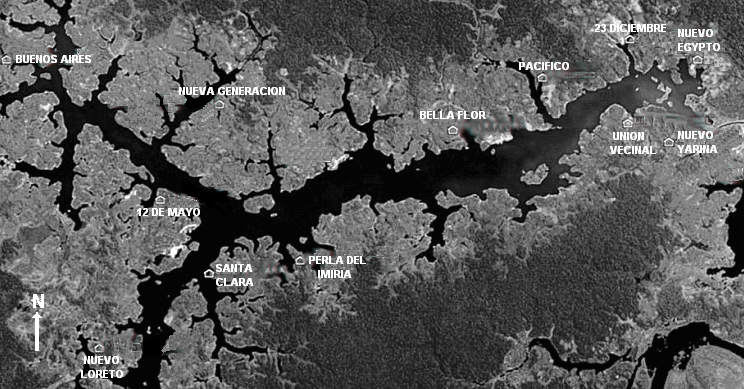

Kilham and his team’s expedition in 2018 traveled the Tamaya River, southeast of Pucallpa, an area known for its abundance of ayahuasca but also for being infested with “narcos, legal and illegal loggers, and thieves.”

The Tamaya River supplies Lake Imiria, an area where ayahuasca grows abundantly and supplies ayahuasca centers in Iquitos and Pucallpa. “The fact that this lake has so much shoreline makes it an ideal place for ayahuasca collection, because you can cut a couple of tons of vine and take it across the river in an hour, something that would take days through the jungle,” Kilham explained.

But if ayahuasca in the wild is plentiful in Lake Imiria, it is even more abundant in nearby Lake Chauya, Kilham explained. However, “it is not easy to get there because there are no roads connecting Chauya to Imiria. If anything, there are waterways that mysteriously open and close, and you have to look for new ways out. In spite of everything, there are harvesters who work in Chauya because there are plenty of lianas (vines) there.”

“In the vicinity of Lake Imiria we find huge lianas weighing several tons, that stand 10 or more meters high, and you can find kilometers and kilometers of them. That is a very different reality from what is depicted in the published articles.”

Is #ayahuasca consumption sustainable? Chris Kilham shows us the conclusions of his research in the Peruvian jungle. Click To TweetFollowing the spirit of his presentation (“From the vine to cup”), Chris Kilham explained the supply chain of how ayahuasca arrives from the jungle to the retreat centers in Iquitos and Pucallpa:

- The harvesters go deep into the jungle, cut the vine, and transport several tons of ayahuasca down the river. They “earn the least but should earn the most.” Each bale of 25 kilos is paid at five soles, a little more than 1 euro. With this amount, about two liters of liquid ayahuasca can be made, after cooking it with five kilos of chacruna.

- After leaving the jungle, the lianas are loaded onto “fast” boats, which arrive at the port of Pucallpa which is the main entry point for ayahuasca. The carriers earn one sol (less than 20 cents) for loading each bale of ayahuasca.

- The bundles are unloaded at the port and put into motor taxis, the typical vehicle of Pucallpa and Iquitos.

- Most of the ayahuasca is taken to distribution warehouses that market the wild liana to the centers.

- Part of this ayahuasca goes to people who do not have centers themselves but prepare the ayahuasca brew for others.

- Other people have specialized in making the brew and exporting it to support the growing demand for ayahuasca ceremonies internationally.

- Sometimes these roles are combined into one. For example, a man with a small center 30 minutes from Pucallpa. He makes his own ayahuasca and also has planted 3,000 vines in his jungle plot.

- On the outskirts of Iquitos one woman runs a thriving business making “concentrated ayahuasca bricks” for export. Each kilo of ayahuasca is equivalent to ten liters of the drink and costs around 630 soles (about 140 euros).

Kilham ended his presentation by citing several centers and shamans who are planting their own lianas in anticipation of a shortage in the future. On the other hand, the ayahuasca boom has encouraged many young people who had left the jungle for the cities to return and recover the plant knowledge of their elders.

Photos by Chris Kilham and article on the expedition published on Linkedin.